Judgment CJEU, 3 September 2014, Deckmyn and Vrijheidsfonds (C-201/13). Request for a preliminary ruling from the Hof van Beroep te Brussel (Belgium).

Judgment CJEU, 3 September 2014, Deckmyn and Vrijheidsfonds (C-201/13). Request for a preliminary ruling from the Hof van Beroep te Brussel (Belgium).

Belgian copyright law provides that “once a work has been lawfully published, its author may not prohibit caricature, parody and pastiche, observing fair practices”. This provision, which existed before the adoption of the InfoSoc Directive 2001/29/CE, and which has not been modified by the implementation of the latter, was clearly subject to interpretation (especially the last three words : “observing fair practices”).

Belgian Courts and Tribunals have therefore progressively established many conditions to be met in order to successfully rely on the exception: the parody had

– to serve a criticism purpose (which was further restricted and interpreted by some authors and case-law as not allowing to parody a work to criticize something else than the work – like using comic book characters to criticize a politician);

– to display an original character;

– to be humorous (or at least, to be carried out with a humorous intention, as wittily nuanced by some authors);

– to use only the original work’s elements that are strictly necessary for the parody (in order not to create confusion with the parodied work);

– not to denigrate the original work;

– not to harm the author;

– neither to constitute a customer poaching nor to be used for commercial goals only (e.g. in advertising for products);…

Needless to say that the uncertainty of this case-law and the many conditions that it imposed made any parody attempt referring to copyrighted material always a tricky exercise (except for well accepted uses such as in newspapers caricatures).

This explains the wording of the preliminary question referred to the CJEU in the Deckmyn case. (C-201/13).

Facts of the case

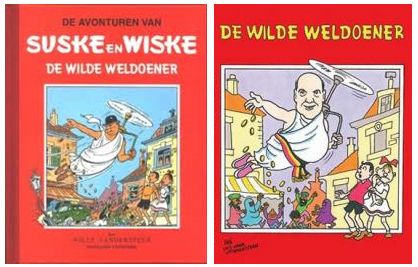

Deckmyn was at the time of the facts member of the Flemish parliament and belongs to the far right and nationalist political party “VlaamsBelang”. He used a modified version of the cover of a comic book of the famous serie Suske en Wiske (Spike and Suzy in English) to openly criticize the city of Gent’s mayor, who Deckmyn accused of “playing the benefactor with the taxpayer’s money to the benefit of foreigners and to the detriment of the city’s livability”. Indeed, the parodied album was entitled ‘De Wilde Weldoener’ (which may roughly be translated as ‘The Compulsive Benefactor’). Amongst others, Deckmyn replaced the head of the “benefactor” with a sketch of the city of Gent’s mayor’s face and replaced the background with people of colour or wearing veils picking up the coins lavishly thrown by the mayor.

The descendants of the comic book’s author Willy Vandersteen sued Deckmyn for copyright infringement, and the latter raised the exception of parody.

In substance, the questions asked to the CJEU can be summarized as follows: are the Belgian parody exception and the corresponding case-law compliant with article 5 paragraph 3, point k) of the Directive which provides that Member States may provide for exceptions or limitations to copyrights in case of “use for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche”?

The concept of parody

The Court first decides that the concept of ‘parody’, which appears in a provision of a directive that does not contain any reference to national laws, must be regarded as an autonomous concept of EU law and must therefore be interpreted uniformly throughout the European Union.

The Court then notices that the Directive does not define the concept of parody and decides that it must be considered in its usual meaning in everyday language, but also taking into account the ratio legis of the exception.

As regards the “usual meaning”, on the basis of the Advocate General’s small etymological study (which consisted in comparing the definitions found in mainstream dictionaries in five languages), the CJEU decides that the essential characteristics of parody are:

– to evoke an existing work, while being noticeably different from it, and;

– to constitute an expression of humour or mockery.

The Court explicitly rejects all the other conditions set out by the referring court in the questions (some of which were referring to the Belgian case law as explained above). It is therefore not required for a work to qualify as a parody to display an original character of its own, to be reasonably attributable to a person other than the author of the original work itself or to relate to this original work or mention the source of the parodied work.

The exception for parody: a fair balance

Interestingly, the Court stresses that the exception has to be interpreted strictly (between the lines, one could read, “and not restrictively by adding conditions that are not provided as such in the Directive”), and that the interpretation must, in any event, enable the effectiveness of the exception thereby established to be safeguarded and its purpose to be observed.

As regards this purpose, the Court reminds us that the rationale of the exception is the freedom of expression. “It is not disputed that parody is an appropriate way to express an opinion” it says. To interpret the exception, this fundamental right must be weighed against the rights and interests of authors, taking into account “all the circumstances of the case”.

Even if it could have stopped its reasoning there, the CJEU carries on with one of those sidesteps to which it lately accustomed us… it indeed gives the referring court its opinion “in case” the referring court would deem that the drawing conveys a discriminatory message as alleged by Vandersteen’s family. In such case, on the basis of the principle of non-discrimination defined in Council Directive 2000/43/EC of 29 June 2000 implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of racial or ethnic origin, which is further provided in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, the holders of the copyrights would have a “legitimate interest” in ensuring that the work protected by copyright is not associated with such a message.

By referring to this “legitimate interest” criterion, is the Court not re-creating a new topic of contention? In the present case, considering that parody is based on the freedom of expression, and given that this fundamental right can be limited to some extent by anti-hatelaws, we can follow the Court in its reasoning: if the parody goes beyond what is protected by the freedom of expression, the exception loses its fundament and the parody becomes an infringement… However, many other “legitimate interests” could be devised and raised in order to try to limit the parody, which might not rely on the freedom of speech limitations.

For instance, the author could claim he objects to any association of his work with any political messages (which is precisely what the author of Spike and Suzy had done in his will): could that be considered as a “legitimate reason”? Would an opposition based on the “moral rights” of the authors (which are not harmonized by the InfoSoc Directive as reminds us the Advocate General Pedro Cruz Villalon in his conclusions) be acceptable?

The scope of copyright exceptions

Finally, about the copyright exceptions system as provided in the InfoSoc Directive in general, it is worth pinpointing this statement of the Court at §16: “An interpretation according to which Member States that have introduced that exception are free to determine the limits [the “parameters” in the Spanish, French and Dutch versions] in an unharmonised manner, which may vary from one Member State to another, would be incompatible with the objective of that directive”.

The Court strikes again at §24: “The fact that Article 5(3)(k)of Directive 2001/29 is an exception does therefore not lead to the scope of that provision being restricted by conditions, such as those set out in paragraph 21 above, which emerge neither from the usual meaning of ‘parody’ in everyday language nor from the wording of that provision”.

From these statements, one could infer the CJEU’s finding that even though Member States are free to select the exceptions they want to implement in their national laws, they seem not free – contrary to what many authors and national lawmakers thought – to limit or reduce the scope of these exceptions, for instance by adding extra-conditions, if this option is not explicitly left to the national lawmakers. In other words, if the exceptions are “à la carte”, adding or excluding ingredients from the dishes does not seem to be allowed in the Court’s view… this could question the drafting of many other copyright exceptions in Belgium and elsewhere!

* Many thanks to Olivier Sasserath for our nice discussions on the case.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Copyright Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer IP Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers think that the importance of legal technology will increase for next year. With Kluwer IP Law you can navigate the increasingly global practice of IP law with specialized, local and cross-border information and tools from every preferred location. Are you, as an IP professional, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer IP Law can support you.